In a recent conversation, an engineering leader highlighted success as how quickly managers jump in and close escalations. Crisis skills matter: calm triage, clear communication, decisive calls. The leaders I admire do that and then make tomorrow quieter.

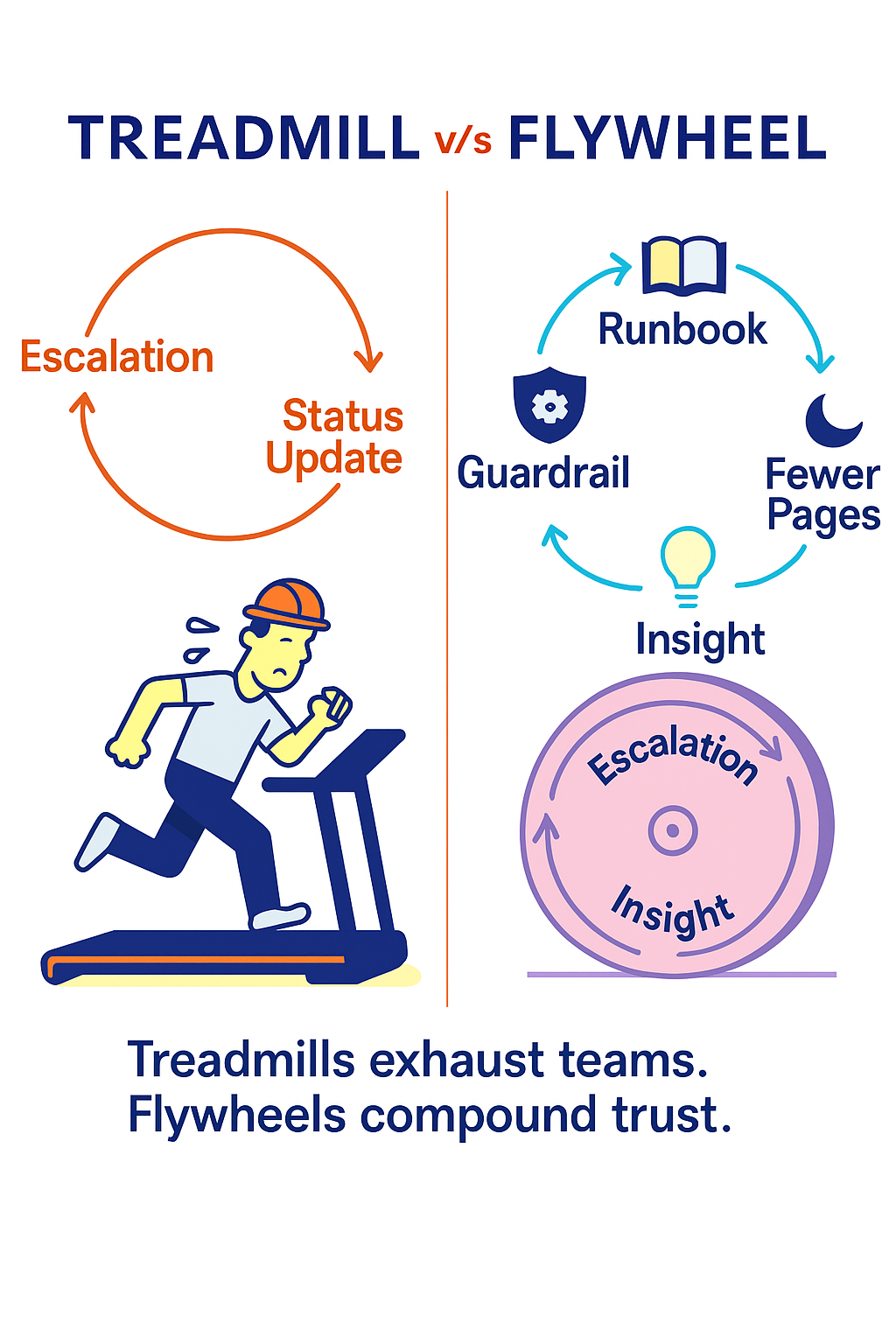

Use the visual above in your mind as you read:

-

Treadmill: escalation → status update → next escalation

-

Flywheel: escalation → insight → guardrail → runbook → fewer pages

The goal is simple. Keep the ability to respond under pressure. Turn every incident into a small step that reduces the chance and impact of the next one.

What the treadmill looks like

-

Status meetings move faster than learning.

-

Fixes rely on a few heroes.

-

The same alerts reappear with new ticket numbers.

-

Confidence rises after a hot fix and fades by the next release.

What the flywheel looks like

-

Each escalation produces one clear insight.

-

Insights become guardrails: SLOs, timeouts, backpressure, flags, canaries, rollback.

-

Guardrails are backed by a short runbook that anyone on call can follow.

-

Fewer pages arrive next week. Confidence accumulates.

Turning an escalation into a flywheel step

Capture the insight

One sentence. Example: “Cache stampede on product detail under peak traffic.”OR,

a 5-whys style root-cause: Example:

- Why did latency and 5xx spike on the product page?

- Many concurrent cache misses triggered recomputes that overloaded the source service.

- Why were there many recomputes at once?

- All pods refreshed the same hot key when the TTL expired at the same moment.

- Why did they all refresh simultaneously?

- No single-flight or request coalescing, and no stale-while-revalidate path.

- Why were those mechanisms missing?

- The caching library used plain GET/SET with a hard TTL and no jitter.

- Why was the library that limited?

- Caching patterns were not standardized; the design checklist lacked “cache truth” and dogpile control, and ownership was unclear.

Add a guardrail

Examples:

- Stale-while-refresh to limit stampedes

- Idempotent handlers and retry policy

- Circuit breaker and explicit timeouts

- SLO with burn alerts

Write the runbook

One page or less. Triggers, commands, owner, rollback, verification checks.Practice once

A team drill. Prove that anyone on call can execute it.Measure fewer pages

Track pages per week and time to rollback. Expect the curve to bend.Guardrail starters that pay off quickly

-

Deploy and release are separate. Use feature flags.

-

Releases are reversible. Keep a tested rollback for each change.

-

Requests fail predictably. Timeouts, budgets, and backoff.

-

Data paths are safe. Idempotency for writes and migrations.

-

Traffic is honest. Rate limits and backpressure at ingress.

-

Observability is ready. Dashboards for latency, errors, saturation, cost, and “what changed”.

A tiny runbook template

-

Trigger: when to use this playbook

-

Checks: dashboards to open

-

Actions: commands or steps

-

Decision points: continue or roll back

-

Rollback: exact steps

-

Validation: what good looks like

-

Owner: who has the baton

Metrics that make tomorrow quieter

-

Pages per week and per person

-

Mean and p95 time to rollback

-

Incidents per change

-

Guardrail changes per week

-

Percentage of changes that are reversible

-

Preventive work completed each sprint

Keep them lightweight. Learn, do not blame.

Roles: manager vs leaders

-

Managers close escalations and keep the queue moving.

Leaders turn escalations into guardrails, training, and fewer pages across teams. They scale prevention.

Anti-patterns to retire

-

Status without a design change

-

Hero mode as a habit

-

Postmortems that name people instead of conditions

-

Big-bang fixes with no rollback

TL;DR

Firefighting builds short term credibility. The best leaders turn that credibility into quieter systems by scaling prevention, not just response.

Choose the flywheel.